Author's Note: We’ll use words like Native, Native American and Indigenous interchangeably as we chat about the connections, caretaking practices and relationships these communities have always had to the places we explore!

At Tinkergarten, we love the Earth and want to preserve our planet for generations to come. We bring this passion into our work as we transform greenspaces to bring joyful, outdoor learning to life!

Care for our planet is a natural extension of outdoor learning, and that includes curiosity about the past, present and future of our outdoor classrooms. We learn our own roles in protecting the planet and about the Native American “original caretakers” of that particular space, particularly the deeply important stewardship and caretaking practices. If you’ve been to a Tinkergarten program, you’ve likely also heard our teachers talk about this connection inspired by a practice called a Land Acknowledgement. This practice is present in many other programs, too.

What do we mean by original caretakers? This is more than a history lesson. In fact, we want to anchor kids in the present and future of Native people today and the ongoing stewardship practices that are critically important to protecting the Earth—our shared home. The first step of this work is understanding the relationship between the original caretakers of the places we explore and how that has shaped what we see today.

This work is deeply meaningful for me and my kids—we are Mvskoke-Seminole and proud of that relationship to the natural world and the ways we see others keeping that wisdom alive. One day, I hope future generations of children will remember us as their ancestors that also loved and cared for our planet.

Indigenous Stewardship

Globally, Indigenous peoples make up less than 5% of the population and protect 80% of the world’s remaining biodiversity. Why is this and what can we learn from it?

Although Indigenous people around the world are not a monolith, many traditional Indigenous practices across tribes, nations and peoples share common values rooted in reverence for living in harmony with nature and the rhythms of local ecosystems. Many consider our planet to be sacred—the Earth holds our past, present and future. Caretaking practices have these values at their core and include sustainability, minimizing impact and preserving and passing down knowledge that protects natural resources.

Our kids and our world need more of this.

“Together, the global community has an opportunity to reorient the way it interacts with nature and build resilience for all through collaborating with and learning from indigenous peoples, the stewards of nature.” United Nations Climate Change

What Does Indigenous Stewardship Look Like Today?

There are some areas where Indigenous people have always been the caretakers of that particular land. There are also spaces being revitalized in partnership with Indigenous stewards using traditional knowledge of the land, plants and environment—restoring a balance of harmony with the rhythms of nature and sustainable practices. These are beautiful examples that show us how protecting and revitalizing Indigenous wisdom impacts everyone, and our planet, for the better.

For many places though, that important relationship and care for the land has been interrupted. Original caretakers and their families are all too often not reflected when we visit public lands, or when we look around local greenspaces, our homes and neighborhoods. For many Native people, access to our own Indigenous wisdom and stewardship practices has been impacted.

It also means that we are all losing a connection to traditional knowledge of how to care for the Earth and restore the balance that will allow our planet to remain our shared home.

That disconnect means our planet suffers, and we fail to honor the important, lasting impact original caretakers make on our shared natural landscape. It also means that today’s Native generations are missing the chance to be known, seen and celebrated for these powerful connections. Finally, it means that we all become disconnected from these ways of caring for the Earth that have been proven over millennia—wisdom that could impact everyone, and our planet, for the better.

That is why it is deeply important to us to be curious, continue to learn and share in the service of honoring the first stewards as well as Native people today. This helps us and kids:

-

Explore outdoors with curiosity about who has come before

-

Celebrate revitalization of Indigenous wisdom in Native communities and beyond

-

Cultivate our own roles as stewards of the past, present and future of our planet— placed within millennia of stewardship history.

Grownups’ Role As Teachers of Stewardship

For our youngest nature explorers, their role in stewardship comes quite naturally! Environmental education expert David Sobel teaches that, for kids, the first step is to fall in love and form a deep connection to the natural world, largely through playful, direct exploration. Sobel urges us to remember that strong stewardship grows when we let that love for the planet form before we ask kids to save it.

Grownups play the critical role of giving the time, access and modeling kids need to nurture that love. And research has unlocked easy, actionable ways to do this. One study examined the lives of the most famous conservationists of all time. The analysis revealed shared patterns in their childhoods. They all:

-

Spent considerable time interacting with nature

-

Had an attachment to a familiar, natural place

-

Benefitted from the modeling and influence of a family member

We can be that influential family member and provide our kids the same opportunities. We can also work to ensure that kids’ attachment to natural places includes caring for the land directly. Over time, we and kids can also come to understand that doing things to learn about and to increase the visibility, restoration and inclusion of Indigenous stewardship is caring for the land, too.

Including Indigenous Stewardship and People in our Work

Below are some examples of ways to nurture a love for the earth, plant seeds of stewardship and make direct connections to the original stewards of the places you care for and explore.

Some of these steps take prior planning and research. Older children can help and learn alongside you, and younger explorers will likely benefit the most if you research independently and share what you’ve learned in easy-to-understand, age-appropriate ways that work for your family.

Set aside and invest time in this research. You may not easily find information at first, but keep digging—this is when we are making the metaphorical mud, and it will be well worth the effort!

Learn about which Native peoples are the first stewards in your area.

- Visit Native Land Digital and search for your ZIP code to learn the names of the Native people that live, or have lived, in your area. Tribes that were removed and relocated hold deep ties to the land and are still reflected and important to include in this learning.

Example: The Tonkawa tribe is from the land where I live just outside of Austin, TX. View the traditional Tonkawa territory map here. -

Where are they today? If you aren’t already familiar, research where those people(s) are today. Some tribes may no longer be with us, but many are thriving, vibrant cultures! Look for websites, books, social media, podcasts and YouTube channels to prioritize first-hand accounts and Native-made resources.

Example: Googling “Tonkawa Tribe” helped me find this official website and Facebook page run by the tribe. I learned the Tonkawa name for themselves is “Tickanwa-tic, meaning: ‘real people’. They were removed from Texas in 1884 and forced to relocate to Oklahoma, where the tribal leadership remains today. -

Learn what plants, species and geography in your area have significance or connections to the Indigenous People: Some knowledge or practices are protected and belong just to the Native people—this is also known as a “closed practice” and that is important to honor, but there is still much that can be learned! Native peoples’ ancestral knowledge is often woven into local, natural remedies and stories that may already be familiar to you.

Example: I learned about the Tonkawa tribe’s creation story involving La Tortuga mountain in Texas from Tonkawa Elder Don Patterson in this YouTube video. My kids and I also learned and love to share with families that the beautyberry plants that grow in our Tinkergarten outdoor classroom have ties to Tonkawa traditions. Beautyberry has healing, medicinal properties used to treat stomach aches. Indigenous wisdom also teaches us that you can crush the leaves and rub them on your skin as a natural insect repellent. -

What stewardship practices are still present? Are there efforts to revitalize caretaking of the land and ancestral knowledge for the Native people? How might this impact the greenspaces you enjoy?

Example: I found a newsletter from last year that shared about a Tonkawa prairie restoration project that includes reintroducing buffalo to the land and learned about the Tonkawa Tribal Environmental Regulatory Project that supports tribal sovereignty to protect the environment and tribal land. -

Support the work: Consider donating to the ongoing, non-profit, Native-led research behind Native Land Digital.

Share what you learn!

- Raise awareness by sharing what you learn about work that is restoring and revitalizing traditional knowledge in Native communities. Reflect on your takeaways about how to support these efforts and grow in your own planet-protecting, care-taking practices. Here are two examples (of many!) that I love:

-

Gabe Sheoships (Cayuse and Walla Walla) is shifting the narrative that forests are just for recreation. Gabe has ensured Native people and knowledge are reflected in Oregon’s Tryon Creek Natural Area by expanding public transportation access to the park, adding books about nature by Indigenous authors, inviting elders and community members to harvest traditional foods and medicine and more. “Like many Indigenous leaders, he acknowledges that humans are in fact a keystone species and there is a mutually beneficial relationship when active land stewardship— through practices like gathering—is encouraged.”

My own takeaways and wonders: Are there nature books by Indigenous authors specific to my area? How can I support seeing them included in parks, schools and libraries? -

The Saginaw Chippewa Indian Tribe and Michigan Department of Natural Resources are partnering to co-manage Sanilac Petroglyphs Historic State Park and the tribe’s sandstone carvings that date back generations. “The tribe’s knowledge is once again steering stewardship of the landscape where the carvings were discovered.”

My own takeaways and wonders: What natural conservation areas in my state are overseen by Native caretakers? Is there work in progress to restore others and, if so, how can I raise awareness for and support those efforts?

-

- Bring Kids Into Your Learning:

-

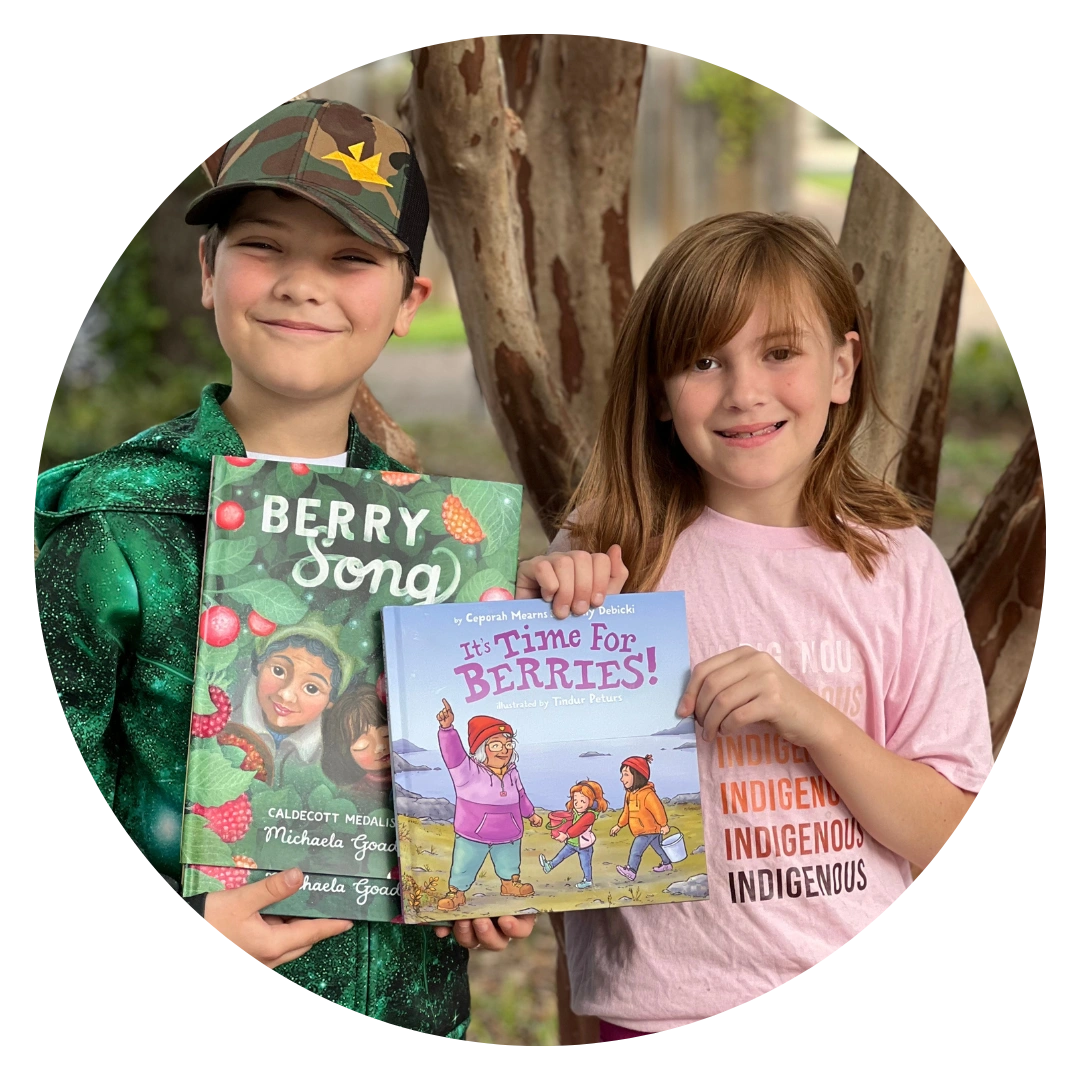

Berry Song, written and illustrated by Caldecott Medalist Michaela Goade (Tlingit and Haida), and It’s Time for Berries, by Ceporah Mearns (Inuit) & Jeremy Debicki (Inuit) and illustrated by Tindur Peturs, are two picture books we love that celebrate Indigenous knowledge, stewardship, foraging with kids, relationships with each other (and the Earth!) and more. Find both of these books and links to purchase from Indigenous-owned bookstore, Birchbark Books, on our Native American Heritage Month book list!

-

Support the work: Follow the authors and illustrators you love on Instagram and let them know how much you appreciate their work—here’s where you can find Michaela Goade and Birchbark Books! Then, request that your local library add their books to the shelves. Consider ordering additional copies from Birchbark Books and donating them to local Little Free Libraries and classrooms, too!

-

- Amplify Indigenous voices and share articles, blogs, social media posts and books about Indigenous stewardship with friends, colleagues, teachers and on social media. Check out this example—I love how innovative the ideas are, and how they are rooted in traditional values:

-

Native Women’s Wilderness featured Bow and Arrow Brewing, a Native-owned craft beer company that partners with other Native companies, procures Indigenous ingredients and is part of the Native Land Beer collaboration that has raised more than $90,000 for Indigenous non-profits focused on ecological stewardship, access to ancestral lands and/or revitalization of traditional agriculture & food ways.

-

- Invite others to join you when attending local, Native-hosted events. Set aside a few minutes to invite playgroups, classmates, friends and anyone in your community. You can even share links and information into local neighborhood, parenting and meetup Facebook groups to help get the word out! Many events include vendor fairs for Native artists, makers and small business owners—a wonderful way to learn about and directly support Indigenous communities!

A better, more inclusive world is within our reach. It will take time and active work to build it, and at times that work may even feel a bit messy—but at Tinkergarten, we know that messy processes often enable the best and most impactful learning. We are grateful to everyone who is willing to roll up their sleeves and get (metaphorically) muddy with us in this work!

At Tinkergarten, we are learners first and are grateful for the opportunity to learn alongside you. Please let us know if you have suggestions about how to make this or any resources we share even more supportive of you and the young explorers you love! We’re eager to cultivate our roles as stewards of the planet, and teachers of stewardship, together.