What metaphor best describes a young child’s developing brain?

Working in schools and on Tinkergarten, I’ve posed this question to many adults. Likely my two most common responses are: a sponge that soaks up knowledge or a blank canvas (aka “tabula rasa”). These responses have their roots in historically held conceptions of child development, but they are not entirely accurate, based on what we know about the brain. The more I work with parents of young children, the more I see this misunderstanding of brain development as a missed opportunity.

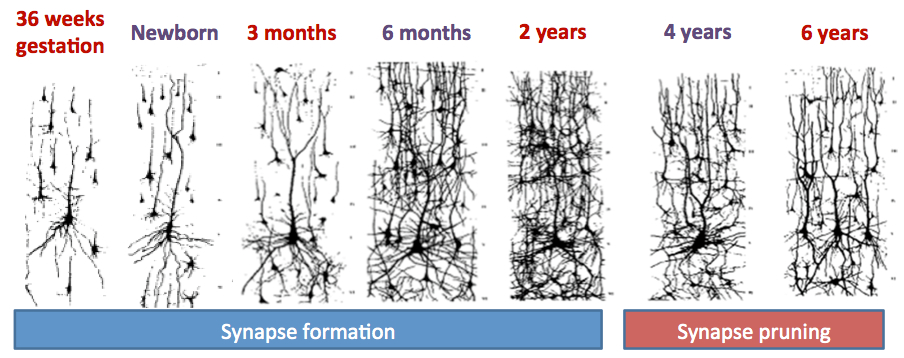

If young brains are neither sponges nor blank canvases, then what’s the right way to think about them? Although I love a good metaphor, a picture says a thousand words or, in this case, a hundred-billion neurons (the number a baby has at birth).

Before we make sense of this image, we can define a few terms that are key in understanding it.

- Neuron: Our brains contain neurons or nerve cells that act as conduits to information, both incoming and outgoing.

- Synapse: Synapses are connections through which two nerve cells pass a chemical or electrical impulse. A series of synapses form a pathway. We pass information through these pathways, enabling us to understand and respond to our world.

- Synaptic overproduction: In the early months of life, humans produce an excess of synapses.

- Synaptic pruning: The process through which the brain abandons connections that are not emphasized by experience.

The image above contains a set of scans of brain tissue at various ages. The black dots we see are neurons and the lines between them the are synapses.

As this shows, my canvas and sponge friends are not totally wrong, but it no longer feels right to see the young brain as either blank or empty. In fact, babies have nearly all of the neurons they will ever have in their brains at birth. In the first two years of life, the focus is not on acquiring more neurons, but on rapidly developing synaptic connections and pathways.

Babies and toddlers produce synapses like mad, creating more than they will need. As they experience the world, the number of synapses will grow from 2,500 per neuron to 15,000 per neuron by age two or three. That 15,000 is approximately double the number in adult brains (Gopnick, et. al, 1999). The preschool years and those that follow are, thus, spent on synaptic pruning—the shedding of pathways that are underused and enhancing those used often. In other words, children use their experiences to help them either strengthen or prune these overproduced and disorganized sets of synapses so that, in time, the brain becomes a more organized and efficient machine. Watch a quick and helpful video from the Harvard University Center on the Developing Child to see how this works.

Just taking a look at the sheer volume and disorder of the two-year-old’s synapses versus her six-year-old counterpart’s gives us a whole new sense of our toddler’s behavior. It’s remarkable that our wee ones hold it together as well as they do, and it’s no wonder that their attention shifts, that they lack capacity to respond quickly to directions, and that their speed to frustration is so high.

In addition to making us more compassionate and patient with our two- and three-year-old friends, these images also made us wonder what conditions help the brain move from the two-year-old image to the six-year-old image and beyond?

- Repetition, repetition, repetition: In our work at Tinkergarten, we think a lot about the kinds of experiences that contribute to successful pruning. We know that connections or pathways that are used repeatedly become stronger and are unlikely to fall off—scientific support for the repetitive behaviors we see in young children’s play. Any parent knows that young children do the same things again and again (sometimes much to the chagrin of our adult brains). This is something we support through repetitive rituals and by regularly revisiting activities in our program. We understand that adult brains seek novelty and parents may wonder why one week’s activity looks so similar to a previous week’s activity. Our answer: kids deserve the chance for the repetition so vital to their growing brains.

Parents can also support brain development when we establish and revisit family traditions and rituals, and when we welcome repetitive behaviors as beneficial. Easing up on our quest for new ideas to allow kids to revisit favorite play experiences is among the best things we can do for our kids.

- Stimulating the senses: We also know that the early childhood brain takes in the external world through the complete range of senses. Use of the senses helps build and strengthen neural connections, as the brain is continuing to develop its architecture and its capacity to not only take in but assimilate new information. Social, emotional, cognitive and physical development are all stimulated when kids have multi-sensory and sensory-rich experiences.

- Fostering positive emotions: Research also tells us that when they experience strong, positive emotions, kids are better able to attend to, make sense of and remember a learning experience. On the flip side, negative emotions and stress not only inhibit these processes. Toxic stress can even contribute to the loss of useful synapses. So, when we create an atmosphere full of wonder and joy in which kids can learn, it isn’t just a technique that feels good, it’s key to creating an environment that support brain development. Hurrah!

As the science reminds us, rather than needing to “receive” knowledge, our young kids need to explore, try, err, try again, and experience as much as possible—all in an environment that is as joyful and as sensory-stimulating as possible. Even though we, as parents, may no longer be painters adding knowledge to a blank canvas, we still can make a great deal of impact. We can set the stage for the development of strong and healthy brain architecture by giving our kids access to rich play environments, engaging materials and plenty of time to explore.

Sounds right, but now what? You can try a few, simple ways to put this all into action:

- Spend more time exploring and tinkering outdoors with your kids. Nature offers a range of sensory stimulation no indoor environment or screen can rival.

- Push the boundaries using your own senses and make a wild mess with your kids. Stomp in a creek. Take your shoes off and feel some mud between your toes. Or, cover yourself in warm beach sand. "Oooo," "ahhh" and show your child how marvelous sensory stimulation can be.

- Learn more about repetitive behaviors kids exhibit in their play. When you notice something repeat, pause before you encourage kids to "move on" or "try something new." Wonder instead about what learning must be happening as they repeat the action.

- Use wonder as much as possible. Act surprised, fascinated and even confused about the things around you. Remember that, for young kids, reality and fantasy are intertwined, and a little fantasy can create a state of wonder. Ask questions that start with "I wonder why..." or "I wonder what would happen if..." and give plenty of time for kids to discover an answer. When you do, you model curiosity and welcome even young kids to activate to help you figure out the world.

- Be silly, goofy and as joyful as you can. Play like no one is watching. Adults rarely err on the side of too silly or joyful for a small child's taste, so go for it. The more positive the emotional environment, the more your child will learn and love your time together.